Introduction

The following article examines the philosophical concept of Kaizen and how it’s adoption can help to enhance productivity and reduce waste within the law enforcement setting. Kaizen has been widely practiced at the corporate and industrial levels, and more specifically in the manufacturing and service sectors,[1] but has had relatively limited impact on public service organizations, other than perhaps in the medical profession, and this to a limited degree and in a sporadic fashion.

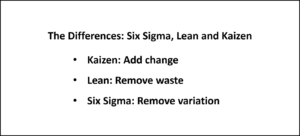

A quick search on the internet will quickly confirm that the references pertaining to the application of Kaizen within the law enforcement setting are extremely sparse. Additionally, many managerial techniques such as Lean and Six-Sigma are frequently conflated with Kaizen. While these alternative processes can contribute to and enhance the effectiveness of a law enforcement agency, there are significant differences. Alternatively, Kaizen has often been reduced to a simple, isolated event format, referred to as a “Kaizen-Blitz,” when this is not at all the function of Kaizen, which is a philosophy of incremental and continuous change. This is necessarily a brief introduction to Kaizen, and later submissions will expand further on this topic. Later topics that will be covered include the various tools relating to Kaizen implementation, change resistance and change management, the Gemba walk, and other associated issues.

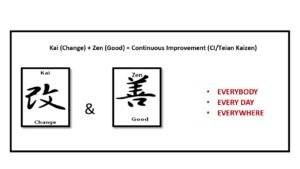

Image source: https://www.deviantart.com/carmenharada/art/KAIZEN-Shodo-Japanese-Caligraphy-700649671

What is Kaizen?

Prior to examining any topic, it is always best to first define it clearly. Kaizen is a Japanese term derived from a compound word Kai referring to “change” and Zen meaning “good.” When combined, like many Japanese compound words, we arrive at a marginally different definition meaning “continuous improvement,” or “CI.”

We utilize the principle or approach of “methodology” for the application of Kaizen to organizational processes. Kaizen is a useful tool for improved procedures, enhanced performance, and efficient results. The Kaizen process of sustained, continuous improvement (CI) also contributes significantly to waste reduction, enhanced safety, and overall effectiveness. Typically, Kaizen projects are low-cost ventures with a maximum budget of $300-400. “Teian” is defined as proposal and represents the suggestions made for changes presented by the work force.

Brief History and background of Kaizen

While the term Kaizen is Japanese, its background is not. The basic underlying concepts of Kaizen philosophy can be traced as far back as the 17th-century scientific thinking and processes of Galileo (1610), Sir Francis Bacon (1620) considered the “Father of the scientific method,” and Sir Isaac Newton (1687), the second scientist to be knighted after Bacon. In the modern era, its roots may be directly traced to the writings of Walter A. Shewhart, a brilliant statistician who advanced the use of the scientific method. Shewhart’s specification, production and inspection processes, were later expanded upon by W. Edwards Deming. Dr. Deming helped the Japanese to revive their devastated post-WW2 industrial economy in 1950. Masaaki Imai made the term famous in 1986 with his book “Kaizen: The Key to Japan’s competitive success.”

Dr. W. Edwards Deming was initially invited to Japan by the American authorities to instruct sampling methods, but he was rapidly recalled. Soon after his return to the United States, in July 1950, Deming was invited back, this time by the Japanese themselves. It eventually took close to a decade for the Japanese to fully understand the importance of ‘Statistical Quality Control,’ or SQC, as taught by Deming. Decades ago, products bearing the label “made in Japan” were rightfully considered to be of vastly inferior quality, in the same way that the “made in China” label is perceived today. They were, finally, able to appreciate the importance of the concepts of target quality and finished quality, and how these concepts were related to the production of superior quality goods and services. For his pioneering, introduction, and implementation of Kaizen in Japan, Dr. Deming was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure by the Emperor of Japan in 1960 for his various contributions.

Quite Ironically, as fate would have it, this business philosophy and approach to manufacturing made Japanese manufacturing companies even more efficient and productive than their American counterparts. This forced companies in the USA to also adopt this business philosophy and develop parallel structures in the late 1980s. This was represented by the development of “Lean Management” and “Six-sigma.”

The following systems are based on Demings’ model of Plan-Do-Study-Act.

Six-Sigma also claims to trace its origins back to Walter A. Shewhart and, before him, to Carl Friedrich Gauss (of the renown Gaussian curve). The term itself is attributed to Motorola engineer Bill Smith, who coined the term in the 1980s. Six Sigma is a process that focuses on minimizing defects and avoiding inconsistencies (aka Kaizen “Mura”). Demings’ process of PDSA will be discussed in a subsequent article.

Lean focuses on the elimination of waste (aka Kaizen “Muda”) or non-value adding activities (NVA). This process can trace its conceptual origins back to Eli Whitney and Samuel Colt’s firearm production, Henry Ford’s assembly line production and finally coming full circle to Toyota’s Total Production Management, or TPM.[2]

Kaizen in the Law Enforcement Setting

Kaizen application in public service organizations (PSOs) has seen extremely limited application and there is precious little research available on the topic. This does not infer, however, that Kaizen cannot serve as a useful addition to the law enforcement toolbox. Kaizen has the potential to offer significant advantages to forward-looking organizations.

In many cases where an attempt has been made to implement the Kaizen philosophy, it has frequently either failed or been met with strong resistance. Alternatively, even when implemented, other problems have arisen and the results have been less than spectacular. This can possibly be attributed to the various obstacles and challenges, including: a failure to establish clear goals, incompatibility with the organizational mindset, complacency, a lack of urgency and motivation, outright inertia, and a failure on the part of the practitioners to fully understand or appreciate the process. In addition to these numerous challenges, the adopting agency, the leadership, or the workforce may undervalue its relevance, and finally, poor managerial implementation practices may also undermine its successful adoption by the workforce.

Kaizen, as you should now be well aware, focuses on a process of continual and sustained evolutionary change. Successful implementation of changes are followed by standardization across the entire organization. There is absolutely no reason that such an approach cannot also benefit the police in the performance of their duties, and furthermore across all sectors of police public service including community relations, patrol, traffic incident management, criminal intelligence, investigations, forensics, enforcement, HR, administration, management, logistical support, and procurement. In brief, Kaizen is versatile enough to be applied to each sector and specialization.

In order to provide the maximum opportunity for successful adoption, the Kaizen process requires training both for those desiring to implement it, as well as those who will be practitioners. Furthermore, clear strategic and operational goals need to be established, i.e. what is it precisely your agency or department is hoping to achieve? Start small and examine the various tools that are available. These can then be parsed and adopted in a fit-for-purpose framework specific to a respective unit, division, department, or agency.

Image source: https://www.thefix.com/how-opioid-epidemic-changing-police-work

Every and any aspect of law enforcement can benefit from the Kaizen process. This applies from administrative procedures and policy development, to training and exercise, and from answering service calls to emergency response. This practice also includes insuring effective, timely, and ethical service in the fulfillment of one’s duties. While Kaizen cannot pretend to resolve all departmental issues at all levels, it can contribute to effective organizational efficiency. The successful implementation of Kaizen should assist an organization in sustaining best practices over the long term.

Kaizen Implementation – Preparation

“You can’t go back and change the beginning, but you can start where you are and change the ending.” – C.S. Lewis

Kaizen has been variously described as a process, a technique, a methodology, or a strategy, among other titles. Since Kaizen is more a philosophy than a concrete methodology or instrumental process, there has been no clear, universal definition of the concept. There are, nevertheless, generally three core features that nearly every proponent of the process agrees upon. These include:

- Teamwork – the process includes everyone in the organization from the patrolman to the dispatcher and from the watch commander all the way up to the Chief Executive.

- Incremental change: changes are small and carried out daily. These types of small changes add up over time resulting in significant improvement within the framework of the organization.

- The Kaizen process must be continuous in order to be successful. It is not a passing fad, or a one-time event, rather a continuous effort on the part of everyone within the organization to improve and change in order to meet the vision, goals, and objectives of the organization through their continuous efforts and contributions. This last principle is perhaps the most difficult to maintain, due to a number of factors including complacency, competing priorities, and the never-ending stream of challenges faced in day-to-day policing.

Additionally, according to Brunet (2003), Kaizen is a collective effort best conducted by small teams with associated work-life benefits for the employees practicing Kaizen.[3] Though this assertion has been contested by other researchers, however, when properly implemented and sustained, it does appear there may be benefits both to the organization and the individual practitioner.

Kaizen – Guiding Principles

There are a number of core guiding principles for Kaizen:

- Always work as a team. It is everybody‘s business. For the approach to be successful, you need to make sure that every member of the organization participates.

- Good processes lead to superior results. Inferior performance is a process problem, not a people problem.

- Focus on small continuous changes.

- To grasp the current situation, you must go and see for yourself (the Gemba Walk).

- Identify the root cause of problems, and then act and correct them.

- Speak with data and manage by facts.

- Eliminate waste: Muda, Mura, Muri, the 3 Mus.[4]

The 10 Commandments (of Kaizen)

These are the generally accepted “10 Commandments of Kaizen:”

- Discard conventional, fixed ideas concerning production.

- Think of how to do it, not why it cannot be done.

- Do not make excuses. Start by questioning current practice.

- Do not seek perfection. Do it immediately, even if for only 50% of the targeted goal.

- Correct mistakes immediately.

- Do not spend money for Kaizen, use your wisdom.

- Wisdom is produced through effort and struggle.

- Ask ― “why” 5 times and seek root causes.

- Seek the wisdom of 10 people rather than the knowledge of 1.

- Kaizen ideas are infinite.

Conclusion

There is more, much more, that still needs to be examined within the context of Kaizen and how it can pertain to a law enforcement setting. The current article hopefully laid out the foundational basic work for the further future development of this interesting topic. This article briefly examined the background and history of Kaizen, the scope of its possible application in a law enforcement setting, some of the common reasons for its failed implementation, and the differences between Kaizen, Lean, and Six Sigma. Finally, the guiding principles and the basic guidelines to bear in mind for successful implementation and adoption have been outlined. It is ultimately the hope that this article has presented some alternative perspectives and ideas as to the possibility of adopting the Kaizen philosophy. The next article will delve into the actual implementation, as well as examining a few case studies in support of its usefulness to law enforcement.

References

Alosani, M. S. & Yusoff, R. Z., 2018. Investigating the Relationship Between Kaizen and Organizational Performance: A Conceptual Framework for Police Agencies. European Journal of Business and Management, 10(24), pp. 12-16.

Bhoi, J. A., Desai, D. A. & Patel, R. M., 2014. The Concept & Methodology of Kaizen. International Journal of Engineering, Development, and Research, 2(1), pp. 812-820.

Brunet, A. P. & New, S., 2003. Kaizen in Japan: An empirical Study. International Journal of Operations & Project Management, 23(12), pp. 1426-1446.

Holland, K., 2014. Kaizen-news.com. [Online]

Available at: https://www.kaizen-news.com/kaikaku/

[Accessed 5 july 2021].

Kaizen Institute India (KII), 2015. What is the difference between Kaizen, Lean & Six Sigma?. [Online]

Available at: https://in.kaizen.com/blog/post/2015/09/11/what-is-the-difference-between-kaizen-lean–six-sigma.html

[Accessed 17 July 2021].

Khan, I. A., 2011. KAIZEN : The Japanese Strategy for Continuous Improvement. International Journal of Business & Management Research, 1(3), pp. 177-184.

latestquality.com, 2021. How to Implement Kaizen in an Organization. [Online]

Available at: https://www.latestquality.com/implement-kaizen-in-an-organization/

[Accessed 6 July 2021].

Lucid Content Team, 2018. What is Kaizen Methodology? Lucidchart Blog. [Online]

Available at: https://www.lucidchart.com/blog/kaizen-methodology

[Accessed 29 June 2021].

Rodriguez, D., 2020. Understanding Kaizen Methodology – Principles, Benefits & Implementation. [Online]

Available at: https://www.invensislearning.com/blog/kaizen-methodology/

[Accessed 27 June 2021].

The content Team, 2018. Gaining the Full Benefits of continuous Improvement. [Online]

Available at: https://sixsigmastats.com/7-wastes-muda-nva/

[Accessed 19 July 2021].

Endnotes:

[1] Alosani, M. S. (2020) ‘Case example of the use of Six Sigma and Kaizen projects in policing services,’ Teaching Public Administration, 38(3), pp. 333–345. doi: 10.1177/0144739420921932.

[2] For a fuller accounting see for example: https://www.6sigma.us/finance/six-sigma-kaizen-lean-differences/

[3] Brunet, A. P. & New, S., 2003. Kaizen in Japan: An empirical Study. International Journal of Operations & Project Management, 23(12), pp. 1426-1446.

[4] Kaizen Institut India (KII), 2015. What is the difference between Kaizen, Lean & Six Sigma?. [Online]

Available at: https://in.kaizen.com/blog/post/2015/09/11/what-is-the-difference-between-kaizen-lean–six-sigma.html [Accessed 17 July 2021].

Featured image credit: https://www.smileworldholiday.com/gallery/%E0%B8%AD%E0%B8%B1%E0%B8%A5%E0%B8%9A%E0%B8%B1%E0%B9%89%E0%B8%A1-japan/

About the Author: Dr. James P. Welch holds a Ph.D. in international criminal law from Leiden University. Dr. James has worked in police, military, and intelligence services for over 50 years. He is a sworn translator/interpreter for the Belgian Federal Police and an Essential Functions Officer (EFO) for the U.S. Department of Defense. Dr. Welch is currently an adjunct professor with Rabdan Academy in the UAE.